Malaysia’s prime minister battles claims of corruption

WHATEVER the truth of them, the accusations levelled against Najib Razak, Malaysia’s prime minister, have astonished a country that some had thought inured to scandal. In early July the Wall Street Journal reported that it had seen documents produced by government investigators suggesting that nearly $700m from companies linked to a troubled state-backed investment fund had been paid into what they believed to be Mr Najib’s personal bank accounts. With worries about an oil-dependent economy, the controversy is the last thing Malaysia needs.

The allegation is that the money was received shortly before the general election in 2013, in which a coalition dominated by Mr Najib’s party, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) scraped home, despite narrowly losing the popular vote. The prime minister helped launch the fund, known as 1MDB, in 2009 and chairs its board of advisers. It has acquired land and power plants, yet has struggled to service debts of around $11 billion. The firm’s affairs were already the subject of official investigations, but until this month no one had claimed to have evidence that the prime minister himself had received any money.

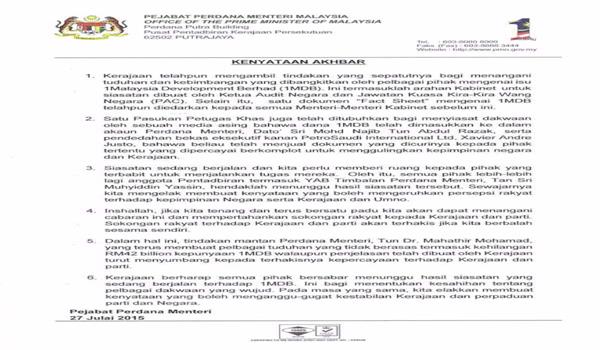

Mr Najib has vigorously denied wrongdoing, including ever having used public money for personal gain. He called the allegations “political sabotage” and blamed Mahathir Mohamad, a nonagenarian UMNO grandee who was prime minister from 1981-2003, for waging a campaign against him. For months Dr Mahathir has been calling for Mr Najib’s resignation, warning that under him, UMNO—which has ruled Malaysia since independence in 1957—may lose an election due by 2018.

The opposition has demanded that the prime minister step down until a special task force, now investigating the allegations, has finished its work. Campaigners known in the past for organising big protest rallies against Malaysia’s heavily gerrymandered electoral system are thinking of calling for fresh demonstrations against the prime minister. But Mr Najib says he is not budging. Outwardly at least he appears still to have his party’s support. A government agency has warned Malaysians against discussing the allegations on social media and has started blocking an indefatigable British website, the Sarawak Report, which has written a lot about 1MDB. Police say they are conducting an inquiry which may uncover the source of the Wall Street Journal’s report.

A boon for Mr Najib is the paucity of obvious substitutes within UMNO. One possibility is Muhyiddin Yassin, a deputy prime minister who had been tipped for the top job when it fell vacant in 2009. Another replacement might be Hishammuddin Hussein, the defence minister and Mr Najib’s cousin (who for now appears loyal). But neither man seems any more likely than Mr Najib to find the vim required to rejuvenate UMNO, which has grown quarrelsome and complacent after six decades in power—and which, in stemming its ebbing popularity, has taken to exploiting old fears among ethnic Malays that their prospects are threatened by Malaysia’s Chinese and Indian minorities.

As for the opposition, it is in disarray. Since its leader, Anwar Ibrahim, was imprisoned on a dubious sodomy charge earlier this year, the opposition coalition has been torn apart by tensions between the DAP, an ethnic-Chinese party, and PAS, a Malay Muslim one, over the latter’s efforts to enforce strict sharia punishments in Kelantan state in the north. Some in PAS now look minded to mend fences with their old foes in the ruling party. Hadi Awang, PAS’s leader, has argued that Islam requires that the Wall Street Journal should produce four witnesses to support its reporting.

All this has distracted attention from Malaysia’s pressing economic problems. Hobbled by low oil prices and slowing Asian economies, the value of the ringgit has sunk to a 16-year low against the dollar. Meanwhile, politicians of all stripes have scrambled to deny that race played a role in scuffles this month in Kuala Lumpur, when a mob of mostly Malay youths confronted the largely ethnic-Chinese employees of an electronics mall—all sparked, apparently, by an instance of shoplifting.

Even if Mr Najib is cleared of wrongdoing, the brouhaha is sapping his standing among ordinary Malaysians. It was already hurt by the recent imposition of a disliked value-added tax. If his popularity keeps sliding, it is difficult to imagine UMNO sticking by him until the next general election. The end of Ramadan, which concluded in Malaysia on July 17th and during which Muslim politicians are supposed to avoid unseemly squabbles, may bring fresh attacks from dissident factions. But Mr Najib is rumoured to be mulling a cabinet reshuffle, presumably to silence critics there. If he can blast through this crisis his opponents may well wonder what, if anything, will bring him down. RPK